By Tobias Bleek

Guggenheim Museum, New York

Boulez's studio in Baden-Baden (© Alfred Schlee, Universal Edition)

It is common practice in music history for composers to return to their earlier works and rewrite them, transcribe them for other instruments or put them into new forms. Nevertheless, that a composer of Boulez’s stature should return to a juvenile work time and again over a period of more than six decades is truly unique. His longstanding creative engagement with Douze Notations pour piano was unforeseeable at the time the work was written, especially as the young, rapidly evolving composer soon considered the state he had reached in it outdated. This becomes clear when we look at the work's publication history. Though Boulez saw his Sonatina for Flute and Piano (early 1946) and the First and Second Piano Sonatas into print in the early 1950s, he left Douze Notations tucked away in his filing cabinet. It was not until 1985 that he had the collection published by Universal Edition in Vienna. By this time the convoluted history of its many arrangements was already long underway.

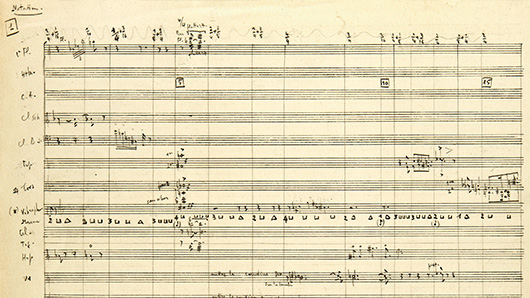

Pierre Boulez: Notation 1 and Notation 2, unpublished orchestral arrangement, 1945-46 (Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel).

The first arrangement of Douze Notations was made shortly after the collection had been composed. The archives of the Paul Sacher Foundation contain the draft of an initial orchestral version prepared in February 1946. The 11 orchestral pieces (Notation 6 was omitted because of its pianistic texture) are direct transcriptions of the versions for piano. Leaving the substance of the originals intact, Boulez merely orchestrated them in the way piano music had customarily been arranged for orchestra. The orchestral writing reveals a wide range of influences. The ‘analytic’ orchestration of the first piece, for example, recalls Anton Webern, whereas the use of the Ondes Martenot [+] points to French forebears and reflects the young Boulez's timbral preferences at the time. In later years, however, he distanced himself from this initial arrangement of Notations, which explains why this student effort, unlike the original piano version, is still unpublished and unperformed.

Boulez returned to his youthful Notations from a new vantage point in the latter half of the 1950s. In 1957 he used material from it in music for a radio play. One year later he drew on it for his Mallarmé cycle, Pli selon pli. For example, a passage from the second section of that work, 'Première Improvisation sur Mallarmé', is based on Notations 5 and 6.

Ondes Martenot (© public domain)

Jean-Louis Barrault and his wife Madeleine Renaud in 1952 (Photograph by Carl van Vechten, from the Van Vechten Collection, Library of Congress)

The ondes martenot ('Martenot waves') is an electronic instrument patented in 1928 by the French musician and inventor Maurice Martenot (1898–1980). It was very popular in Paris during the 1930s and 1940s, when it was used not only by composers such as Olivier Messiaen, Arthur Honegger and Darius Milhaud but also in a great many film soundtracks and theatre scores. Pierre Boulez composed an unpublished quartet for ondes martenot in summer 1945 and employed the instrument again in his first orchestral arrangement of Notations, likewise unpublished. To make ends meet, he even worked for a while as an ondist at the Folies Bergère, the popular Parisian cabaret and music hall. Finally, the instrument was also responsible for his friendship with the French mime, stage director and impresario Jean-Louis Barrault (1910–1994). In autumn 1946 Barrault hired Boulez to play the ondes martenot in a performance of Arthur Honegger's incidental music for Hamlet. A short while later Boulez took charge of the stage music for the Compagnie Renaud-Barrault at the Théâtre Marigny – a position he held until 1958.

Pierre Boulez and Patrice Chéreau 2007 (Universal Edition/Eric Marinitsch)

Boulez's major involvement with the material of Notations, and the true metamorphosis of the ideas presented there in rough outline, began in the late 1970s. In the background were his acoustical experiments at the IRCAM [+] in Paris and his intense study of the music of Richard Wagner. In 1976 he conducted Patrice Chéreau's groundbreaking new production of the Ring at the Bayreuth Festival. Over the next three years Boulez continued to spend part of the summer in Bayreuth conducting the repeat performances of this so-called 'Centenary Ring'. It was in this context, in 1978, that he lit on the idea of returning to his early work, still lying in his filing cabinet. He started to produce a second orchestral arrangement on days when he did not have to conduct or rehearse.

IRCAM in Paris (© public domain)

IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et de Coordination Acoustique/Musique) is an institute founded in Paris by Pierre Boulez for research in music and acoustics. Established at the request of the then French President Georges Pompidou, it opened its doors near the Centre Pompidou in 1977, after years of preparation, and was personally headed by Boulez until 1991. IRCAM is a novel institution in which composers, scientists, engineers and computer programmers work together on transdisciplinary projects. Its original structure and research programme reflected the creative interests of its founder. Under Boulez's direction, for instance, special emphasis was placed on live electronics, that is, on electro-acoustical music produced by musicians in real time during a performance. Boulez was also keenly interested in the acoustic properties of instrumental sounds – a field that influenced the way he handled the large orchestra in his later version of Notations.

Daniel Barenboim on the genesis and creation of the Notations pour orchestre. Interview with Wolfgang Schaufler (Universal Edition). Go to the complete interview.

Pierre Boulez conducts the LUCERNE FESTIVAL ACADEMY orchestra (Georg Anderhub, LUCERNE FESTIVAL)

The resultant Notations pour orchestre, which remains unfinished, is thus a fresh recasting of the early piano pieces. The ideas stated there in rough outline function like germ cells, unfolding in the light of possibilities raised by the medium of the orchestra. The proliferation, expansion and multiplication of the basic material are so far-reaching that the connections between the piano pieces and their orchestral counterparts often become evident only after deeper study. For example, Boulez developed the roughly one-minute piano piece Notation 7 into an orchestral piece of some nine minutes' duration.

The orchestral versions of Notations 1-4 were premièred in June 1980, with Daniel Barenboim conducting the Orchestre de Paris. Some 17 years later Boulez developed an orchestral version of Notation 7, which Barenboim premièred with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on 14 January 1999 (it was subsequently revised). And as recently as summer 2012, the composer, now 87 years old, confided that he was working on an orchestral version of Notation 8.

Guggenheim Museum, New York

In short, the Notations project was Pierre Boulez's most longstanding 'work in progress'. Still incomplete at the time of his death, it reflects his fascination with the metamorphosis and further evolution of his own musical creations:

Emmanouil Vlitakis, Funktion und Farbe: Klang und Instrumentation in ausgewählten Kompositionen der zweiten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts: Lachenmann – Boulez – Ligeti – Grisey (Hofheim: Wolke, 2008), pp. 73–130.