Between Messiaen and Leibowitz – Boulez's musical apprenticeship

In September 1943 the 18-year-old Pierre Boulez, after spending a year studying mathematics, moved from Lyons to Paris in order to devote himself entirely to music. In the same month he officially enrolled in Georges Dandelot's preparatory harmony class at the Paris Conservatoire. He also continued to take private piano lessons, and in early 1944 he began to study counterpoint privately with ![]() . But the encounter that proved crucial to his compositional career came at the end of his first year in Paris.

. But the encounter that proved crucial to his compositional career came at the end of his first year in Paris.

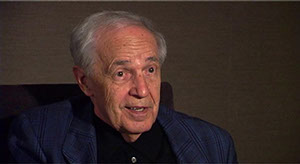

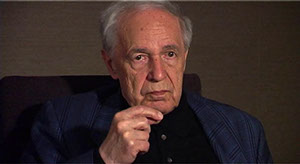

Pierre Boulez and Olivier Messiaen, November 1988 (Photo: Ralph Fassey)Pierre Boulez on ear training with MessiaenPierre Boulez on Messiaen's harmony class and private analysis coursesStudies with Messiaen

On 28 June 1944 the 19-year-old Boulez introduced himself to ![]() .[1] By that time Messiaen had already earned a reputation as an organist and composer and, after returning from German war imprisonment in 1941, headed a class in harmony at the Conservatoire National Supérieur. He expressed his willingness to take on a student 17 years his junior.

.[1] By that time Messiaen had already earned a reputation as an organist and composer and, after returning from German war imprisonment in 1941, headed a class in harmony at the Conservatoire National Supérieur. He expressed his willingness to take on a student 17 years his junior.

In October 1944, after a few private preparatory lessons, Boulez entered Messiaen's class, which he completed with a first prize in early summer the following year. The main focus of the lessons, which took place several times a week, was on training the ear and the musical imagination, creating an awareness of harmony, and examining music from an analytical standpoint. The works studied ranged from Monteverdi to Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky. Messiaen, a passionate teacher, also acquainted his students with non-European music. Boulez recalls first hearing Balinese music in early 1945 on recordings played in Messiaen's class.

Messiaen must have quickly recognised Boulez's extraordinary talent, as just a few weeks after accepting him into the harmony class he invited the young man to take additional private classes in composition and musical analysis. These friendly meetings, which took place once or twice a month at the home of the musician and Egyptologist Guy Bernard-Delapierre, were designed to lead especially talented students 'deeper into the heart of music' [2] Boulez attended them from December 1944 to spring 1946. In these surroundings, free from the pressure of academic instruction, he found important inspiration for his own composing. Playing on 'a magnificent grand piano',[3] Messiaen acquainted the hand-picked students with his analyses of orchestral works by Stravinsky (Le sacre du printemps, Petrushka), Debussy (La mer, Jeux, Nocturnes) and Ravel (Ma mère l'oye). He also discussed pieces which at the time were neither heard in concert nor taught in academic curricula: Bartók's Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, string quartets and violin sonatas, Schoenberg's Pierrot lunaire and Berg's Lyric Suite. Finally he also showed his private pupils one of his own major creations: the piano cycle Vingt regards sur l'Enfant-Jésus (1944).

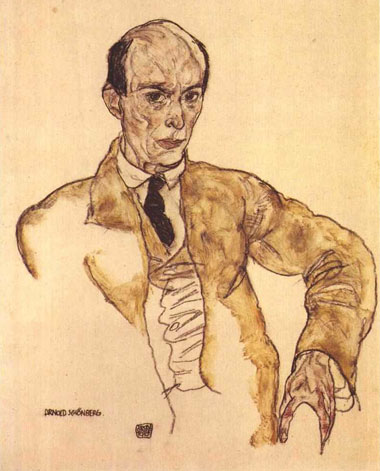

René Leibowitz (Paul Sacher Foundation, Basel)Private lessons with Leibowitz

A second seminal event in Boulez's artistic development took place in February 1945 when the barely 20-year-old musician heard Schoenberg's op. 26 wind quintet and op. 23 piano pieces at the home of the Parisian arts patron Claude Halphen. The organiser of this private recital and the conductor of the wind quintet was ![]() . During the German occupation, this composer, writer and teacher had secretly promoted the music of the blacklisted

. During the German occupation, this composer, writer and teacher had secretly promoted the music of the blacklisted

![]() in Paris. Once the city was liberated in late August 1944, he became the leading champion and mediator of the 12-note method and the music of Arnold Schoenberg in France.

in Paris. Once the city was liberated in late August 1944, he became the leading champion and mediator of the 12-note method and the music of Arnold Schoenberg in France.

The encounter with Schoenberg's ![]() was an eye-opening experience. As Boulez later put it, he instantly realised that 'another musical universe existed outside Messiaen's class'.[4] Together with some fellow students, including

was an eye-opening experience. As Boulez later put it, he instantly realised that 'another musical universe existed outside Messiaen's class'.[4] Together with some fellow students, including ![]() and

and ![]() , he asked Leibowitz to accept him as a pupil. The private analysis lessons probably began in early 1945. The Messiaen pupils met at Leibowitz's home on Saturday mornings to learn the basics of 12-note technique and to dissect dodecaphonic compositions under his supervision. By summer 1946 they had studied pieces by Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg. The order in which they studied the works and the precise point at which Leibowitz began to analyse Webern's music is uncertain. What is certain is that by late 1945 Boulez had gained his first concert experience of the Viennese composer who would have the greatest impact on him. On 5 December Leibowitz conducted Webern's Symphony op. 21 in a concert at the Paris Conservatoire.[5] To the young composer, then already at work on Douze Notations, the encounter with Webern's 12-note masterpiece was a creative epiphany with far-reaching consequences.

, he asked Leibowitz to accept him as a pupil. The private analysis lessons probably began in early 1945. The Messiaen pupils met at Leibowitz's home on Saturday mornings to learn the basics of 12-note technique and to dissect dodecaphonic compositions under his supervision. By summer 1946 they had studied pieces by Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg. The order in which they studied the works and the precise point at which Leibowitz began to analyse Webern's music is uncertain. What is certain is that by late 1945 Boulez had gained his first concert experience of the Viennese composer who would have the greatest impact on him. On 5 December Leibowitz conducted Webern's Symphony op. 21 in a concert at the Paris Conservatoire.[5] To the young composer, then already at work on Douze Notations, the encounter with Webern's 12-note masterpiece was a creative epiphany with far-reaching consequences.

Pierre Boulez on Olivier Messiaen and René LeibowitzMessiaen vs. Leibowitz

During his brief apprenticeship, Messiaen and Leibowitz had introduced Boulez to conflicting musical universes and mindsets. Not only were the two men important intermediaries, they also inspired the young composer to find his own musical language. In retrospect, however, Boulez viewed their impact on his artistic development and musical thought quite differently. To the end of his life he remained attached to his great teacher Messiaen, despite occasional tensions and disagreements, and often emphasised his signal importance. But being averse to all forms of dogma, the young composer already began to rebel against his mentor Leibowitz as early as summer 1946. From then on he had an extremely critical view of Leibowitz's achievements. ![]()

Pierre Boulez on the genesis and design of Douze Notations12-note row of Douze NotationsAn homage to the number 12

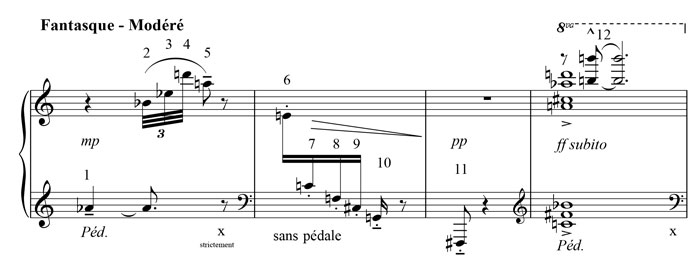

Boulez's Douze Notations for piano were written during the final phase of his private studies with Leibowitz and Messiaen. Having discovered the 12-note method in early 1945, the 20-year-old composer first tried it out unsystematically in several still unpublished piano pieces and a quartet for ![]() . Then, for the first time, he used it as the basis of an entire piece. The design of Notations can be seen as a musical homage to the number 12: it consists of 12 short pieces, each of which is 12 bars long. Each of these miniatures has its own distinctive character, with sharp contrasts not only between the pieces but sometimes within a single piece. The element they all have in common is a 12-note row that is employed in different ways throughout the pieces, thereby creating coherence on the level of the musical material (see the music example). But Notations is not a rigidly 12-note work, for Boulez treats the technique he learned from Leibowitz with great freedom. The row is used not only horizontally and vertically but also in permutation, split and fragmented into segments. There are also many repeated notes, clusters, glissandos and various forms of ostinato.

. Then, for the first time, he used it as the basis of an entire piece. The design of Notations can be seen as a musical homage to the number 12: it consists of 12 short pieces, each of which is 12 bars long. Each of these miniatures has its own distinctive character, with sharp contrasts not only between the pieces but sometimes within a single piece. The element they all have in common is a 12-note row that is employed in different ways throughout the pieces, thereby creating coherence on the level of the musical material (see the music example). But Notations is not a rigidly 12-note work, for Boulez treats the technique he learned from Leibowitz with great freedom. The row is used not only horizontally and vertically but also in permutation, split and fragmented into segments. There are also many repeated notes, clusters, glissandos and various forms of ostinato.

Pierre Boulez, Notation 1, mm. 1-4Influences and traces

For the young Boulez, the work on Notations was a sort of compositional stocktaking. The pieces reflect not only his creative adoption of 12-note technique and Messiaen's rhythmic procedures, but also his study of the music of Arnold Schoenberg, Igor Stravinsky, André Jolivet, Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók and Anton Webern as well as non-European music. For example, the horizontal exposition of the 12-note row in the opening bars of Notation 1 (see illustration) recalls the waltz from Schoenberg's op. 23 piano pieces, but the expression mark 'fantasque et modéré' is clearly reminiscent of Debussy. Yet, the piece's asymmetrical rhythms obviously draw on Messiaen's concept of free meter ('musique amesurée'), for the music is based on a short basic unit (the 16th note/semiquavers) and its compounds rather than a regular meter. Almost every measure has a different length (from six to 21 16ths/semiquavers) and the barlines, rather than indicating metrical stresses, merely serve for purposes of guidance. Finally, the concise expression and meticulous shape of each figure point to Boulez's study of the Viennese School, the enthusiasm he then felt for Schoenberg's piano pieces and his discovery of the terse music of Anton Webern.

Despite these many allusions, the young composer of Douze Notations already speaks with his own voice. Rather than adopting his chosen models intact, he transforms and amalgamates them. As a result, defining features of Boulez's compositional style are already evident in this collection of musical miniatures.

Further reading

- Susanne Gärtner, Werkstatt-Spuren: Die Sonatine von Pierre Boulez: Eine Studie zu Lehrzeit und Frühwerk (Bern: Peter Lang, 2008), chap. 'Pierre Boulez' Lehrzeit', pp. 17–123.

- Robert Nemcek, Untersuchungen zum frühen Klavierschaffen von Pierre Boulez (Kassel: Gustav Bosse, 1998).

Notes

[1] Peter Hill and Nigel Simeone, Messiaen (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), p.138.

[2] Messiaen's words in a letter to his own student Jean-Louis Martinet (22 September 1943). Quoted from ibid., p.132.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Susanne Gärtner, Werkstatt-Spuren: Die Sonatine von Pierre Boulez: Eine Studie zu Lehrzeit und Frühwerk (Bern: Peter Lang, 2008), p.49.

[5] The programme also included Leibowitz's own Chamber Concerto, op. 10, and Schoenberg's Herzgewächse, in which Boulez himself played the harmonium.

A journeyman composition

Written by Tobias Bleek

Musical metamorphoses

Composing within narrow confines

A journeyman composition

History and context

Credits

Boulez video interview

Inside the score